As part of the Hostages of the System campaign, we present the stories of people who spent time in detention centers for migrants in Poland. Using online communication tools, we would like to start a public discussion about detention and alternative measures to detention. In our opinion, the right to detain foreigners is too often abused.

Those touching accounts were penned down by Magdalena Olszewska, a writer and journalist. Stories were illustrated by Daniel Chmielewski.

Some names and details are changed. Our clients wish to remain anonymous.

Hamid →

Yoofi →

Raisa →

Malika →

Nyan →

Hamid`s story

My eldest son rarely left his room. He would spend days in bed, covering his head with a blanket. His arms and legs trembled whenever he saw guards but he would not run – he just froze in place. He was the one who was assaulted by government people in our former country

I used to run a shop in my country. I have no idea what it is like there now. I closed down my business and left it behind when they took me. They were security service agents – I know that because one of them even flashed me with an ID. They said that I wanted to cause a war to break out in the country, that I was instigating people to riot. I did not confirm that so they locked me up for several weeks.

It was all because I once went to a meeting of the opposition out of curiosity. Later on, I attended such meetings quite often and eventually started supporting that party. We wanted to change something. Back in our country, bribes are the only way to get anything done and it was also for a bribe that they let me go in the end. I do not know how much more I would have endured if my uncle had not paid that money. Even talking about it hurts.

My wife was terrified when she saw me, I was black and blue all over. She cried and she knew straightaway that we needed to run, I did not even have to convince her of that. The situation was made even more urgent because of a recent assault on our eldest son, who is nine, by government people. He ran back home and did not say a word to us, he just quivered all over.

We left immediately after I regained my ability to move normally. We fled through Russia and we stopped at the Polish-Ukrainian border. We vainly tried to cross it several dozen times. Every morning we would wake up early, pack up our things, leave the key at the hostel’s front desk and go to the border with all our children. My wife carried our youngest son, who was three at the time and who got tired quickly, while I carried all our luggage. When it was our turn to be interviewed, I explained the situation we found ourselves in and asked to be considered a refugee but they made us go back to Ukraine every time. We would try again in the afternoon and then check in at the same hostel for one more night. At last, they let us through after two months.

I remember that I felt at ease for the first time in a long time as they drove us to our destination in a car and I looked through the window. We had left our previous life behind.

While in court, we felt out of our depth, awed by all those judge’s gowns. The translator who was assigned to us for the duration of the proceedings asked us whether we would like to be transferred to a refugee centre. Obviously, we wanted that, realising that it was the first step made by refugees in Poland. No one told us that it would be an isolated and guarded facility.

We ended up in a building surrounded by a sheet metal fence which was much higher than I was. It must have been two metres high. Its top inclined inwards and there was barbed wire there. There were also monitoring cameras here and there. There was little room between the wall of the building and the fence, barely enough for a playground. Our children played there as we were kept in the centre for more than half a year.

My eldest son rarely left his room. He would spend days in bed, covering his head with a blanket. His arms and legs trembled whenever he saw guards but he would not run – he just froze in place. He was the one who was assaulted by government people in our former country. We were offered the assistance of a child psychologist. A female guard proposed this to us when she saw what was happening to our child when he sees a guard. Those guards were not aggressive at all.

My wife and I were not doing all that well ourselves but we could not just hide under a blanket. It broke my heart whenever my children asked me to give them some fruit, even just one to split between the four of them, and I was helpless to do so. I was completely helpless.

I dream of a day when my wife is able to safely go outside on her own and handle things by herself or, if she wants to, find a job she likes. I would like to become a driver in Poland. One of my sons would like to become a doctor one day and others just change their minds all the time, one day wanting to be football players, then programmers, then musicians. To me, the most important thing is for them to be able to cope with their memories so that they never wake up in the middle of the night, covered in cold sweat. The way I do.

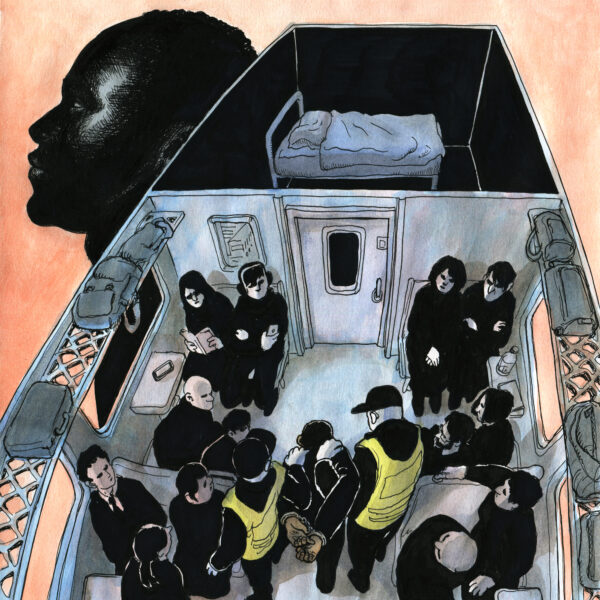

Yoofi`s story

Waiting is the worst. You just wait and wait and then you wait some more. It’s even worse than if you were actually in prison because you don’t even know what you are doing time for or what your sentence is. I saw grown-up men lying down on the floor and crying because they did not know what would happen to them. One of them even said that he would rather be dead,

I am from Ghana, from a nomadic tribe. We travel from place to place, looking for the best pastures for our cattle. In our world, a cow’s life is often worth more than a man’s life – there are bands of armed robbers taking animals from farmers and nomads such as ourselves. If we resist, blood is spilt.

I saw my cousin get killed like that. He was quick to anger so he tried to fight and they just bashed his skull in. This is not something discussed or written about openly because all media in Ghana are state-controlled. Besides, it’s not a matter of any interest for anyone in the world.

My father died when I was little. My mother raised my brothers and myself on her own. I heard that she had fled to Burkina Faso so maybe we will meet again someday. I do not know where my brothers are, both have gone missing. I fear that they might be dead because they were in an area where fighting was taking place.

To score a goal

I have always wanted to be a football player. I have practiced a lot ever since I was a kid and imagined myself scoring a decisive goal in a World Cup match. When I was seventeen, a recruitment agent from Europe noticed me and I ended up in Moldova. I played in the major league there but there were few opportunities to develop there so I accepted a proposal for being transferred to Poland without a moment’s hesitation.

It was only after my arrival that I understood that the man who was supposed to find a football club for me in Poland was only taking money from me while not getting anything done.

I filed for permanent residence with a Polish office and started looking for a team on my own. I lived with a flatmate and sometimes went to parties with him. One day, we went to another city for a friend’s birthday party. As we were coming back on an early train, dozing off like one would after a night of partying, we were suddenly woken up by two people wearing uniforms. They wanted to see our IDs.

Detained on a train

It was then that I learned that a negative decision had been taken with regard to my stay in Poland two months earlier and that my stay in the country had been illegal ever since. I was not notified of this in any way, there had been no letter, no e-mail, and no phone call from the office.

They twisted my arms behind my back and handcuffed me. I was frightened because I had never been handcuffed before and it hurt. People on the train looked at me like I was some sort of a criminal – a black hooligan apprehended at last. They put me in the back of a van and drove me to the airport to the border guard. There, they stripped me naked for a pat-down. I feel like crying every time I recall those events. I mean, I was not aggressive in any way, I cooperated.

I was locked away for the night in a detention facility. The smell of urine there was so strong it was nauseating. The window was slightly ajar but it only made the room colder. It was February and I was wearing light clothes which were barely warm enough to go to a party and back again. I slept on the concrete floor with only a thin mattress and a blanket. In the morning, I got a cup of tea and a slice of bread with butter. The cup was sticky with grime.

They said I had no right to an attorney

They undressed me again in the afternoon and then took me to court. I had no attorney. They said I was not entitled to one and I believed them.

After the proceedings were over, they transported me to a guarded centre for foreigners. They undressed me for a third time. I think they were making sure I was not carrying a concealed weapon.

I do not know why that place is called a guarded centre. Why not just call a spade a spade and say it’s a prison? As far as going for a walk is concerned, you can circle the facility and that’s that. Our cows back in Ghana had more space to themselves. Guards watch over you at all times. If you row with a guard or with another inmate, they may hit you, handcuff you, or put you in solitary confinement. It’s a dark room without windows and with a bed as the only piece of furniture.

The food is all right and served on clean plates but the portions are so small that they would not be enough even for a woman, let alone a young man such as myself. Pangs of hunger wake you up at night even if you manage to fall asleep after the last visit of the guards for the day. Breakfast is served at nine. It’s difficult to kill time until then – people just walk up and down corridors anxiously. It’s best to save some bread from the canteen and take it to your room. I think I’ve lost around 10 kilograms during my stay there.

Waiting is the worst

Waiting is the worst. You just wait and wait and then you wait some more. It’s even worse than if you were actually in prison because you don’t even know what you are doing time for or what your sentence is. I saw grown-up men lying down on the floor and crying because they did not know what would happen to them. One of them even said that he would rather be dead. I did not cry over my misfortune any more after I learned more about how they ended up there.

My case is still pending. Most of my friends stopped contacting me after I was sent to the centre. I wish I could go back to playing football professionally. I could even start at the very bottom, from the fifth league.

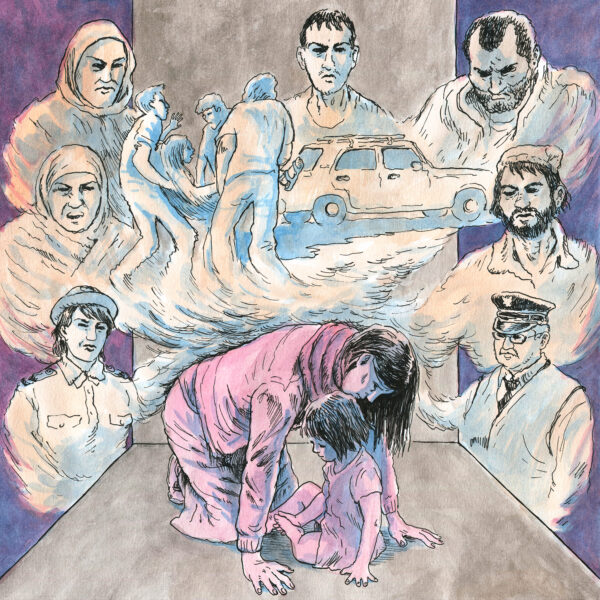

Raisa`s story

No one had been in the detention centre in Kętrzyn for as long as I. When we left, my daughter was almost two years old. I was locked up and without any hope and going crazy.

When I was sixteen, they kidnapped me to force me into marriage. This is how it’s done in Chechnya – they grabbed my hands, carried me into the car, and put me inside. I didn’t know what was happening, it took place so quickly. Now I think it had all been planned behind my back. My mother had been long dead, and my father was drunk all the time, as if he wasn’t there at all. The older brothers probably wanted to get me out of the house, so they made a deal with my aunt.

He was an adult, thirty-three years old. I was a work and sex machine. Sometimes I managed to go to school, but not very often, because I had to clean, cook and take care of his disabled son. After a year my aunt, my father’s sister, visited me. I was pale and very weak. Auntie went to talk to my husband’s mother. It all turned into a big row and in the end she took me away from there. I got a divorce.

He told me to have an abortion

A divorced woman doesn’t have a chance to remarry in Chechnya, but I was happy when, years later, I met someone I believed to be a wonderful man. I knew he had a family, but I was hoping that we would at least get a local Muslim ceremony. When I got pregnant, he told me to have an abortion. He threatened to hurt me if I didn’t. I couldn’t go to the police, as the police is against ones like me.

It’s strictly forbidden to have a child born out of wedlock in our country. It’s a greater offence to have a bastard than to have an abortion. It’s immoral and so embarrassing for the family that I should die for it. In our country, women are killed for it, and it’s believed to be normal. So normal that no one is surprised when such a woman disappears, and no one looks for her or reports it.

Officially, these are disappearances, although everyone knows it was a husband, a father or a brother who killed them driven by shame. This is the only way to wash away the dishonour. I had to run away before my brothers discovered that I was pregnant. I was also afraid of the father of my unborn daughter, Sofia.

I was four months pregnant when I came to Europe, to Poland. There were a lot of people on the border in Brest. My fifth attempt at crossing the border proved successful.

I covered my stomach with a sweatshirt

They took me to a foreigners’ centre, I shared a room with three other girls. In the centre I met a woman who said that I was very similar to a certain Ramzan. I replied reflexively that this was my brother’s name. I just said it, I didn’t think about it. It wasn’t until later that I got scared. It turned out that her daughter had married him.

I have a big, wide sweatshirt with a zipper. From then on, I wore it all the time so that no one would see my stomach. It wasn’t easy to hide, because I wasn’t alone in the room. My stomach was growing, and my fear grew by the week. Finally I escaped to Germany. There were other women who went there, and I joined them.

In Germany nobody recognized me, but after eight months they deported me to Poland, with my six-month-old daughter.

The journey took three days. After crossing the border, they first took us to another centre, where we stayed overnight, at all times under video surveillance. Later we drove for what seemed like forever. So long that we both cried from tiredness.

Take off your clothes and squat

They changed the car three times and searched us every time. On the border, in the evening and in Kętrzyn. Wherever they brought us, they ordered us to take off our clothes and squat. They also searched my bag. I had already asked them what they were looking for. I told them I had nothing and that they should take what I had and leave me alone.

I was kept in a locked centre for foreigners for a year and five months. At first, I didn’t want to accept that I was locked away, I rebelled. The guards ordered me to go to the room, and I went back to the hallway. It was impossible to take a step without supervision. You want to take the child outside, at least for a moment, a guard follows you. You go to the bathroom, the camera follows you.

I was slowly going crazy

No one had been in the detention centre in Kętrzyn for as long as I. When we left, my daughter was almost two years old. I was there for so long, locked up and without any hope that I was already starting to go crazy. I hugged my daughter for hours and cried, but the psychologist always said that I was fine.

It’s better in an open centre, you can go out, but there’s no point. I would like to send my child to a kindergarten, go to work, but I am not allowed to. It is very difficult to spend all the time in this one room.

Sometimes I wake up thinking that everything will work out, everything will turn out fine. But most of the time I force myself to get out of bed only because I have to take care of my daughter. I am as if detached from reality, so confused, and I act mechanically like a robot. Once, a guard in uniform came here to the centre. I locked myself in the toilet with my daughter and, crying, I called SIP. I was terrified that they had already come to deport us.

If they deport us, we will die

What’s going to happen? I don’t know. I have been wondering for four years and I still don’t know. They’ll probably deport us, send us to Moscow. I will get off the plane with the child and what then? Where should I go, what should I do? Without registration of residence, nobody will hire me, the child will not receive medical care, and I cannot register. When you register, they always send a note about it to Chechnya, that’s the law. And we have to disappear, otherwise my family or her father will find us.

Malika`s story

Over half a year after he regained his freedom, my son is still plagued by nightmares. Almost every night he wakes up crying. The most frequently recurring dreams are about men wearing masks who beat him up. I myself also suffer from nightmares. On such occasions, I dream that somebody is strangling me and that somebody always turns out to be Polish Border Guard.

Back in Chechnya, we lived in a house which sported a garden full of fruit trees – there were peaches, nectarines, apples, and nuts. I taught English in an elementary school and, in addition to that, organized private classes. My husband worked as a taxi driver. We were not particularly wealthy but I never had to worry about what I would give my children to eat the way I sometimes do now. We were just a regular family.

All of a sudden, a dozen or so years after [the Chechen] war, when it seemed that we could resume peaceful life without fear, the authorities apparently decided that all men in my husband’s family posed a threat to them. His elder brother and cousin took part in the second Chechen war.

First, they killed the cousin. Then the brother was taken away, beaten up, and tortured until he broke down and eventually died. After that, they killed my husband’s other brother. They also started taking my husband away. They would break into our house in the middle of the night. Sometimes there was as many of them as ten. They wore black masks and there were no insignia on their uniforms.

Back then, my son was already seven and he was capable of understanding many things. He saw them break down the door to our house, push him down to the floor, and then drag him to a room. He heard his father being struck and howling in agony. Then there would be silence all of a sudden.

I told him that I could not stand living in fear like that anymore

I was never certain where my husband was or if he would return. When they took him the last time, I was pregnant and the risk of losing the baby was high. I do not know how I managed to give birth to a healthy child in the end. My husband met his second son for the first time after almost a year had passed.

When he did return to us in the end, there were scars and open wounds all over his body. I said that I had had enough and I could not live like that anymore. We fled soon afterwards. We did it one night close to the end of March. It was quite cold.

We travelled to Moscow by car and then took a train to Belarus. It was crowded in Brest and there is only one train per day so either you managed to squeeze your way on board of it or you stayed where you were. You need to buy a round trip ticket because if you didn’t manage to make your way into Poland and were send back, there would be nowhere to buy one.

We met people who had been sent away with nothing thirty times in a row. Sometimes even forty. If you were able to afford it, you got private accommodation for 12 Euro or stayed at a hotel for 25 Euro. If you could not afford it, you just slept at the station.

We got incredibly lucky – they let us through on our second attempt. We were sent to a reception centre in Biała Podlaska and then we moved to Warsaw. Our son started going to school there and quickly learned Polish. I was happy that he was at peace.

After we received a negative decision, we escaped to Germany

Our application for international protection was denied and we were obliged to leave Poland and return to Chechnya but nobody told us that it was not the end for us, that we could appeal against the decision. We were so frightened that we simply fled to Germany. We know now that it was a serious mistake but we just panicked.

After four months in Germany, we were sent back to Poland and ended up in a detention center. Every time we changed means of transport, which probably happened around five times, my husband and I were taken for a screening separately. I had to undress completely, even removing my bra and panties, and then squat so that they could make sure that I wasn’t hiding anything between my legs. Fortunately, they only made our children take off their jackets and shoes. It was a cold September and I was worried that they would get cold. Our elder son wept all the way.

We underwent one last search after we arrived at the center. They checked our luggage and took away our phones for safekeeping. A small room served as our accommodation.

They carried out a head count at 8 a.m. and then at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m.

There was a nursery school in a classroom on a higher floor. There was one teacher for all children, regardless of their age, and all classes were held in one room. Being a teacher myself, I asked the teacher about his curriculum. He had none.

Even though there was enough food, I always had to cook it some more because I did not want my children to eat half-raw meat and undercooked potatoes.

They counted us at 8 a.m., 7 p.m., and 10 p.m. They didn’t even bother to knock – they would just barge in through the door and count us as if we were heads of cattle to be taken stock of. Once, I asked a guard: “What if I am in the middle of changing my clothes?” He just shrugged his shoulders and left. I moved the wardrobe to have at least some privacy.

Our eldest son refused to leave the bed. I brought meals and a chamber pot to him. He lost eight kilos, becoming all eyes and bones. We had waited for three months for an appointment with a psychiatrist. We were delivered there under guard.

The doctor prescribed some antidepressants for him and made a note in the documents of the case saying that a child in such a state should not be kept locked away.

My son is still plagued by nightmares

I asked to talk to the warden. He said: “The kid is taking his medicines and he will be all right, don’t blow this out of proportion, lady.” So I wrote an official request for being released. They answered that it was a provocation and that it was us who ordered our child to stay in the room all the time because we wanted to be set free earlier.

I persisted until they eventually set up another meeting with the psychiatrist. The doctor once again wrote that every day at the center worsens our son’s phobias. It was then that they let us go.

Over half a year after he regained his freedom, my son is still plagued by nightmares. Almost every night he wakes up crying. The most frequently recurring dreams are about men wearing masks who beat him up. I myself also suffer from nightmares. On such occasions, I dream that somebody is strangling me and that somebody always turns out to be Polish Border Guard

Nyan`s story

At the center, everyone has a story to tell. Those who have been smuggled into Poland illegally show the greatest determination and, at the same time, are the most desperate. They usually had to sell everything they had and some of them spent 15 years’ worth of savings to be able to pay ten thousand dollars for such a transport. They travelled in terrible conditions, sometimes risking death of exhaustion. They arrived in Poland from Pakistan or Afghanistan and it was usually a one-way trip for them. Each one of them had his own reasons and his own fears.

I was raised on a beautiful Asian island cherished by tourists. It was a wonderful place but it felt kind of cramped for me. I wanted to see the world. First, I spent two years studying in Australia and then I started dreaming of going to Europe. I came to Poland in 2007, did a B.A. a course, and met a girl who gave birth to our daughter in 2011. That’s what happened to me in a nutshell.

Monica’s pregnancy was a difficult one, there had been some complications and she had to undergo Caesarean section. She felt terrible after giving birth to our child and she wasn’t even able to walk. The situation had grown so serious that we had to move house to live closer to the hospital. I looked after her and the child, whom I fed, changed, bathed, and tucked in for sleep in the evening. I was happy to be a dad.

I looked after our child and my ailing partner on my own so I was not able to continue studying at the university. Because of that, I lost my student visa. I was afraid that if I reported it, I would be sent back to my home country and my girlfriend would be left without anyone to take care of her. I did not realize that I had the right to apply for a humanitarian residence permit thanks to having a family in Poland.

After some time, Monica felt better and decided to resume working while I stayed home with our child.

I went to Cracow in July 2017. Two policemen came up to me and asked me to show them my ID. I drew their attention because my clothing was too thick for the season. I left the hotel early in the morning and I put a jacket on when it had been colder but the weather turned warm later on during the day. They must have thought that I was in Poland for the first time and they decided to check what I was doing there. My residence permit was no longer valid then.

Afterwards, already in a courtroom, a representative of the Border Guard said that they had not been able to confirm my identity because I did not have a valid identity document with me. I was sent to a detention center in Lesznowola. The judge said that I was going to spend three months there. It was nine months.

On my way to the center I asked one of the guards about what I was supposed to do and he said to me: “Listen, my job is to send you back home and you are asking me for advice?” After that, however, he explained to me how my situation could develop from there and even provided me with the names of some non-governmental organizations which could help me. I arrived at my destination late in the evening after the sun had already set and I was a little bit taken aback at the sight of a gate and fence which seemed very much like a prison to me.

There were around forty men locked away together in confined space. You begin to feel claustrophobic and in dire need of more room for yourself when you can’t be out of sight of others even for a moment, when there are constantly people passing by you, when you are nudged and shoved aside, and there are people having conversations right next to you all the time. Under such circumstances, even a tiny thing can result in you losing it and getting very angry. We were aware that there were cameras everywhere but arguments never seemed to end, sometimes even getting pretty violent.

There were four computers for the forty of us. Sometimes one of them would break down. Each one of us had around half an hour of internet access per day. During those 30 minutes, you had to answer your emails, contact your lawyer, and check up on your family, all the time with a line of irritated people behind your back and with somebody rushing you. Once, a man from Iran did not leave the computer station when he was supposed to. He only exceeded the time assigned to him by maybe a minute or two, he just needed some more time to send his messages and sign out from his email account. A big man from Nigeria got so angry because of that that they started a fight. You could also barter away your internet access time for cigarettes at a rate of three or four of them for half an hour.

You do get a phone, an old model without a camera, but you have to have a SIM card of your own. To get one, you need to register at a cellular operator’s sales point which may prove difficult if you are kept in a guarded center to which you were delivered straight from the border. Somebody can also send you a SIM card to the center but who is supposed to do that when you have not got to know anybody in Poland yet? Many people there have no one to ask for help.

You can order goods from a shop twice a week. There are women there who make a list and then bring what you ordered to you. However, you can’t use money from your bank account – you need to give them cash. It doesn’t matter if you have been at the center for a month or for a year, you are allowed to spend a total of PLN 500 and not a coin more. That is not much, especially in light of the fact that you also have to buy additional food and, in my case, cigarettes for that. I spent my money in a very economical way but I ran out of it after 3 months anyway.

At the center, everyone has a story to tell. Those who have been smuggled into Poland illegally show the greatest determination and, at the same time, are the most desperate. They usually had to sell everything they had and some of them spent 15 years’ worth of savings to be able to pay ten thousand dollars for such a transport. They travelled in terrible conditions, sometimes risking death of exhaustion. They arrived in Poland from Pakistan or Afghanistan and it was usually a one-way trip for them. Each one of them had his own reasons and his own fears.

In my case, I only failed to fulfil an administrative obligation so there is nothing terrible awaiting me in my country but I’m very afraid of being sent back to it anyway. My relationship with Monica eventually turned sour and we broke up. In spite of that, we managed to remain friends with each other. She was offered a promotion and moved to Germany with our daughter and I wasn’t able to go with them. That’s the price which I paid for my short-sightedness.

There’s no way for me to be allowed to stay in Poland for humanitarian reasons now due to having a family here as my child is not in the country on an everyday basis. I could go back to my country, wait until I am no longer forbidden to return to Poland and apply for a visa but then I would have to describe my previous visits to Europe. If I lie and then they discover it, and they will definitely discover it sooner or later, I will never be allowed to return to Europe. If I tell the truth, that I stayed in Europe for a time illegally and ended up in a detention center, the end result is going to be the same. This is why I keep appealing against decisions taken by different courts and that is why I have stayed in Poland. I can’t join my daughter in Germany, I can’t even pay a visit to her there because I would have to cross the border illegally. Monica and our daughter visit Poland regularly and, thanks to that, I have contact with her not only online. I count days between her visits. Officially, I can’t start working and I don’t want to start working illegally. That would be too risky. And so I ended up in a vicious cycle. Every month, I report to the Office for Foreigners on Taborowa in Warsaw. Other than that, I just wonder around the city, constantly thinking about my daughter.